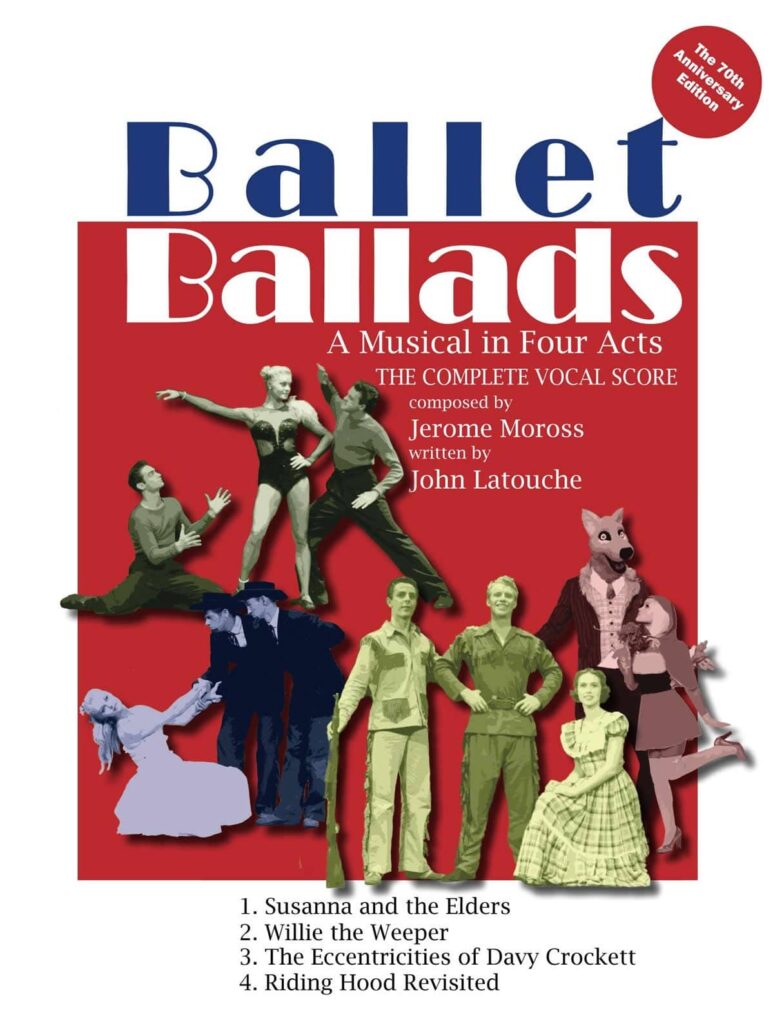

BALLET BALLADS

THE SHOW

A HISTORY OF THE MUSICAL

NOTES ON BALLET BALLADS

BY MARIANA WHITMER

Introduction

During the pre-World War II years of heightened populism and nationalistic fervor, lyricist John Latouche (1914-1956), collaborated with composer Jerome Moross (1913-1983), to create the novel production, Ballet Ballads. As Latouche wrote in 1948, “Our intention was to blend several elements of the American theatrical, dance and musical heritage into a pattern adapted to the contemporary stage.” The two artists initially encountered disapproval and condescension: “Any theme we mentioned to our friends that seemed suitable to the styles we wished to use met with an odd reaction from them: the more austere critics dismissed our subjects as suspiciously resembling ‘Americana.'” Latouche and Moross addressed this disdainful reaction head-on by blatantly adapting American topics — using idioms from American musical styles. As Latouche sarcastically noted, “We decided to avoid as much as possible the quaint and cute overtones implicit in such a label [“Americana”] and to aim for the direct statement. Three musical styles suggested themselves as native material: the revival hymn; jazz, blues and boogie; and the folk song.”1

Moross and Latouche created the four theater pieces over the years from 1940 through 1946: “Susanna and the Elders” (1940-41), “Willie the Weeper” (1945), “The Eccentricities of Davy Crockett” (1946), and “Riding Hood Revisited” (1945-46). The individual pieces differ in character; “Susanna” and “Davy Crockett” are lively and upbeat, while “Willie” is dark and brooding. The gospel-influenced music in “Susanna” contrasts with the jazz and blues idioms of “Willie.” The larger-than-life persona of Davy Crockett is enhanced by the folk-infused melodies that highlight the fabled and simplistic nature of the work.

As Moross and Latouche wrote in the introduction to the original publication, the collection of works known as Ballet Ballads “were intended to fuse the arts of text, music and dance into a new dramatic unity.”2 The music is formally constructed, with nods to the conventions of opera; yet the singing and movement are combined in a unique manner that resists description. Although the descriptor “ballet” is included in the title, these works have also been called “dance cantatas,” “dance-operas,” and most recently, a “hybrid form.”3 The individual movements relate a narrative, yet contain no spoken dialogue, so, in that respect, the label of opera is highly appropriate. As Moross later explained, “Attempts had been made previously to use both singing and dancing in a mixture, but always with the two ingredients carefully separated.”4

In Ballet Ballads the singers are incorporated into the movement; they are onstage, and at times they interact with the dancers. This fusion of singing and dancing was designed to occur progressively from the first work to the last, as the relationship between the dancers and singers develops. From separate roles in Susanna and the Elders, where Dancing Susanna and Singing Susanna appear together, but do not interact, to the complete combination of singing and dancing in Riding Hood Revisited, the connection between the two grows steadily.

Moross was partial to classic music forms, such as the strophic song, the four-movement symphony, or the theme and variations, so each segment of Ballet Ballads is carefully constructed. Susanna and the Elders is somewhat of an exception, since it is cast as a revival meeting, and the choral narrative dominates in a primarily through-composed arrangement. Each story, however, features at least one mesmerizing musical number that suspends the narrative briefly, allowing introspection, elaboration, or commentary on the action. “Willie the Weeper,” “The Eccentricities of Davy Crockett,” and “Riding Hood Revisited” offer several such instances, and, in these occasions when the music and text come together, the virtuosity of Moross’s and Latouche’s combined talents shines.

Susanna and the Elders

This work is based on a traditional and well-known Biblical story, yet it introduces the unexpected combination of dancing and singing that Moross and Latouche develop throughout Ballet Ballads. As Latouche later explained, it was “[i]ntended as a curtain-raiser to familiarize the audience with the form we were using.”5 Inspired by the apocryphal work added to the Book of Daniel, Latouche explained the work’s conception: “I shaped my lines after the earthy psalmodies I had absorbed during a Virginia childhood. Mr. Moross derived his inspiration, although not his melodies, from the raucous tonalities of the Bible Belt.”6

The stage is set as a revivalist camp meeting with the Preacher at the podium and a congregation seated in the bleachers. Susanna and the Elders is divided into eight distinct movements, with a nominal finale at the end of the fourth movement, dividing the work into two “acts.” In the music, Moross infused elements of gospel singing, including call and response, syncopation, and hymn-like textures with much repetition. The chorus also comments on the Preacher’s narration of the parable with interjections of, “Praise His name!” and, at times, claps along. These narrative portions of the work contrast musically with commentary on the action, as when Susanna sings her reaction to the Elders’ accusation. Her solo aria during the trial is distinctively lyrical and technically challenging in its range, suggesting a conception like that of a classical opera.

As Susanna and the Elders act out the parable in dance, members of the stage congregation gradually leave their seats and become characters in the story. Initially, a singing Susanna emerges, giving voice to the dancing Susanna, and, later, the entire choral congregation steps down to become the people of Israel. A dancing Angel appears and moves behind the singing Preacher, becoming his more active counterpart while offering inspiration. At the end, the congregation returns to the bleachers, while the Angel and dancing Susanna sit below the pulpit, and the singers, the Preacher and singing Susanna, remain on the podium. Thus, both singers and dancers represent the main characters, yet the performers only minimally acknowledge their counterparts. There is little interaction between the two.

Willie the Weeper

While Susanna provides the conservative opener, Willie the Weeper offers a sexy, eyebrow-raising contrast. As Latouche later explained, Willie “was selected as the second theme primarily because of its musical contrast with the other two, and also because of the lyrical contrast, which concerns itself with the desires and fears of the present day, rather than [of] a nostalgic past.”7 Dancer Sharry Underwood, who performed in the premiere of Ballet Ballads, described the contrast between the first two works: “The show’s center of gravity changes . . . from uptight-upright to low-down-and-out. Where Susanna is concerned with public opinions and attitudes of society, Willie concentrates on one man’s self-esteem.”8

Latouche included original lyrics from the ballads of “Willie the Weeper” and “Cocaine Lil” into the text to establish the fundamental narration. Thus, the story tells of a strange marijuana-induced dream that Willie has in a series of seven episodes, each depicting a different Willie persona. The music of Willie the Weeper may have been inspired by Moross’s early song, “Cocaine Lil” (n.d.) which exists only in manuscript. The intensely chromatic construction, the abundance of chord clusters, and the text, all relate this early composition to Willie the Weeper, but the connection is especially noticeable in the last episode, where “Cocaine Lil” is introduced.

The overall approach was intended to evoke the traveling vaudeville shows prevalent in the 1930s.9 The music is often unified by a repeated “boogie-blues bass” in the accompaniment, as Latouche noted, “intentionally monotonous to highlight the repetitious frenzy of Willie’s reefer dreams.” Jazzy and syncopated rhythms are utilized throughout, with contrasting tempi to underscore the different Willie personalities. Frequent chromaticism in the melodic line further enhances the bluesy feel.

Each episode offers a unique musical atmosphere to highlight Willie’s mood and persona, which alter as the marijuana reefer goes out and is then relit. In the first two episodes, “Rich Willie” and “Baffled Willie,” Moross creates a frenetic atmosphere to emphasize Willie’s excitement and confusion, respectively. These two movements, along with “Famous Willie,” “Big Willie,” and “Contented Willie,” are all set in duple meter, while those of the less upstanding Willies — Lonely and Sexy, are characterized by triple rhythms and more chromatic melodic lines. At the end, it all dissolves in the dream: “Poor dreamy Willie, dreamed himself silly.”

Willie the Weeper ends as it began, consistent with the evocation of a dream from which the audience is now waking. The vocal line from the beginning re-emerges, as does the accompaniment. It is as if Moross composed the music to get as far away stylistically as possible from its initial presentation in the introduction, only to bring it back gradually. This segment of Ballet Ballads always seems to garner the most attention, probably due to its provocative subject matter.

The performance of Willie the Weeper requires a double ensemble, with half of the cast singing and half of them dancing, and often freely combined. Willie is presented as two characters: a singing Willie, described by Moross as a “decrepit tenor,” and his alter ego, a dancing Willie, an “elegant dancer.”10 Singing Willie and Dancing Willie often appear together onstage, and, at the beginning, their movements are identical. By Episode 6, “Contented Willie,” they are dancing together, but only Singing Willie is serenading. Throughout Willie the Weeper, the singers and the dancers freely intermingle, although there is still a division of the principals (Willie, Cocaine Lil) into singers and dancers.

The Eccentricities of Davy Crockett

As suggested by the word “eccentricities” in the title, Latouche and Moross did not intend this work to be historically factual, but based on a legend. The bluesy and sexy chromaticism of Willie the Weeper is gone, replaced by pure and wholesome Americana, with diatonic melodies and a wonderfully hopeful narrative. Moross later revealed that he had conceived “The Eccentricities of Davy Crockett” as a four-movement symphony.11 This formal construction is difficult to discern in the music, since it is not as clearly defined as the expected classical structure. Based on narrative content, as well as on tempo, texture, and melodic materials, the various movements may be understood by roughly grouping the 14 scenarios from Davy’s life. The first “movement” includes the introduction and Davy’s life story from when he was born, through his youth, courtship, and marriage to Sally Ann. It ends with the couple’s journeying to the frontier. The second movement comprises the most active musical numbers, where Davy battles Indians and saves the world from Halley’s Comet, approximating a Scherzo and Trio. In between these two conflicts, Sally Ann sings a lovely lyrical ode to Davy (“You’re My Yellow Flower”), and Davy hooks a mermaid, who attempts to lure him into the river. These two romantic segments form the contrasting Trio. In the third movement, Davy goes on a bear hunt and encounters the Ghost Bear, who urges him to consider others who have been hunted for their religious or political actions. In this somber segment, approximating the slower contrasting movement of a classical symphony (Latouche actually referred to it as an adagio), the Ghost Bear conjures specific individuals, and Davy is inspired to run for congress. The last movement is a fast-paced presentation of the bickering and dealing by the Jacksonian Congress, ending with Davy throwing in his high hat and topcoat in a gesture of resignation. The final segment, “Davy Becomes a Legend,” is the Coda. Davy describes his need to return to a wandering lifestyle in a lovely solo, “Riding on a Breeze,” which is followed by a return to the music and scenery from the very beginning.

Throughout “The Eccentricities of Davy Crockett,” Moross set Latouche’s lyrics in a simplistic fashion, tending toward the folksy. He fashioned melodies characterized by an abundance of thirds and set in syncopated rhythms. The music approximates but does not directly quote American folk tunes, creating a pastoral atmosphere throughout. Moross’s setting of the Indian War is surprisingly free of the stereotypical reiterated fifths often used to signify Native Americans, and instead of the forceful duple meter (with the emphasis on the first beat), Moross utilizes triple meter.

The overall formal music structure organizes the combination of free dramatic elements. With the singers participating fully in the choreography, the final unity between singing and dancing is achieved. Only during the bear hunt are the singers offstage, while the dancers represent the hunters. Latouche later described the “interweaving” of the various arts: “The chorus arbitrarily portrays frontiersmen, the singing walls of a house, trees, Congressmen, and whatever else is necessary; the dancers communicate the plot; Davey [sic] and his wife both sing and dance their roles . . . [incorporating the] completely free use of all the theatrical elements . . . to project the legend of Davey’s life.”12

Riding Hood Revisited

The fourth work, Riding Rood Revisited, is the most amusing of the works offered in Ballet Ballads. In August 1944, writing to Latouche with ideas for “Riding Rood Revisited”, Moross originally imagined that Little Red Riding Hood’s father, the Woodchopper, would accompany and rescue Red from the Wolf. Yet, early on, Moross’s overall approach was slightly different from that of the original story, as he communicated to Latouche: “The whole atmosphere must be a combination of the Disney Silly Symphony and a slightly lascivious version of an American children’s classic.”13 When scripting the story, Latouche steered the narrative in an even more ribald direction with the introduction of the Good Humor Man, who woos Riding Hood and replaces the Woodchopper as the rescuer. “Riding Rood Revisited” features a seductive Riding Hood (intentionally leaving out the fairy tale epithet “Red”), a sexy, mature Wolf, and an unconventional Grandmother who lusts after the Wolf.

The work is subtitled A Silly Symphony in E flat major, perhaps the only time that Moross actually identified a key signature in his works. Corresponding somewhat to the classical symphonic form, are four movements distinctively titled “Overture,” “Rhumba,” “Pastorale” and “Waltz and Variations,” with an added “Coda.” The first two movements set the scene musically and narratively. The Overture introduces the awakening forest at the onset of spring. During the Rhumba, Mrs. (not “Mother”) Nature, with the help of a chorus and The Three Clouds, remarks on the messiness of the season. The offbeat rhythms of the dance evoke the disorganized atmosphere of the “cross pollination” voiced by Mrs. Nature. The Three Clouds represent the forest or nature throughout the performance, acting as Mrs. Nature’s helpers in advancing the narrative.

Riding Hood, a “modern teen-ager with a bored manner,” (as indicated in the score) is introduced in the Pastorale. The bucolic setting in this section signals good clean living, contrasting with the urban location to which the Wolf will take Riding Hood in the next movement. Mrs. Nature summons the Good Humor Man, who falls instantly for Riding Hood and succeeds in courting her. The music reflects the simplistic atmosphere; there is no pretense, just a humble declaration of love. The rhythms are straightforward, and the melody that accompanies the Good Humor Man is characteristic of ice cream vendors.

The seduction of Riding Hood by the Wolf, who is described as Viennese, unfolds in the fourth movement, the “Waltz and Variations.” Dancing is prominent in this section, as Moross’s theme is a lively waltz befitting the Wolf’s culture and refinement. While the Wolf and Riding Hood dance, the chorus, Mrs. Nature, and The Three Clouds describe and comment on the action. Moross treats the theme throughout the nine variations in unique and inventive ways to depict the narrative musically. At times he alters the music by embellishing the melody or by changing the meter. The music of the Good Humor Man is uniquely steady and never syncopated. In more than one instance, Moross juxtaposes duple and triple meter in different voices to enhance the confusion in the narrative.

Throughout Ballet Ballads, Latouche animated the objects in the stories. Thus, the trees in “Susanna,” the walls of the frontier home in Davy Crockett, and the flowers and clouds in “Riding Hood Revisited” all sing and dance. This personification of the entities that surround the players heightens the fantastic character of these theatrical works. As everyone and everything participate in the singing and dancing, Moross’s music and Latouche’s lyrics create a unique experience grounded in Americana, but within a novel theatrical approach.

Ballet Ballads has never been performed in its entirety; that is, with all four balletic works performed together. “Susanna and the Elders” was first performed in Hollywood in 1941 as a concert piece (without dance or costumes) by the Hollywood Theatre Alliance, a small ensemble conducted by noted studio music director and film composer Alfred Newman. Moross wrote a review of the concert, but only briefly mentioned his own work, describing it as an “oratorio . . . meant as an entertainment piece for chorus and orchestra.”14

On May 9, 1948, “Susanna and the Elders,” “Willie the Weeper” and “The Eccentricities of Davy Crockett” opened as a set at Maxine Elliott’s Theatre in New York City. It was produced by The Experimental Theatre, Inc., which generally produced unfamiliar works on a subscription basis, sponsored by the American National Theatre and Academy (ANTA). After six performances, Ballet Ballads moved to The Music Box Theatre on May 18 and closed on July 10.

Ballet Ballads was later performed in Los Angeles, from October 8 through November 21, 1950, at the Century Theatre, featuring only “Susanna,” “Willie” and “Davy.” From September 22 through October 5, 1954, the work was presented at the Berlin Festwochen as Bilderbogen aus Amerika (Portraits from America), the only time Ballet Ballads was performed outside the United States. These performances included Riding Hood Revisited in place of The Eccentricities of Davy Crockett. On January 4, 1961, Ballet Ballads was revived at the East 74th Street Theatre in New York City. This presentation featured “Riding Hood Revisited” (substituting for “Susanna”), “Willie the Weeper” and “The Eccentricities of Davy Crockett,” refreshed by new and improved choreography.

In 1966 CBS commissioned Moross to orchestrate Ballet Ballads for a television production that never took place. Ultimately, Moross orchestrated the fourth movement of “Riding Hood Revisited” and titled it Variations on a Waltz for Orchestra. This work was recorded in 1993 by the London Symphony Orchestra, and as bibliographer Charles Turner pointed out, knowing the Latouche version of “Riding Hood” (which is different from the original fairy tale) makes the listening experience much more enjoyable.15 With the exception of “Willie the Weeper,”0 which was performed and recorded (the only commercial recording) with Moross’s full orchestration in 2000 in Hot Springs, Arkansas, Ballet Ballads has not been staged since 1961.

1 John Latouche, “Items Called Ballet Ballads: Some Notes on their Prolonged Journey to The New Music Box,” New York Times, June 6, 1948, X1.

2 Jerome Moross and John Latouche, “A Note on Production,” Ballet Ballads (New York: Chappell & Co., Inc., 1949).

3 These descriptors appear, respectively, in the booklet accompanying Jerome Moross: Frankie and Johnny performed by the Hot Springs Music Festival Symphony Orchestra conducted by Richard Rosenberg, Naxos American Classics (8.559086); a production note in the published edition (Chappell Music, Inc. 1949); and Charles Turner, “Jerome Moross: An Introduction and Annotated Worklist,” Notes (Philadelphia: Music Library Association), 61:3 (March 2005), 65.

4 Jerome Moross, “Ballet Ballads Revisited,” Unpublished document.

5 Latouche, “Items Called Ballet Ballads,” op. cit.

6 I bid.

7 I bid.

8 Sharry Underwood, Ballet Ballads, Dance Chronicle, 9:3 (1986), 302.

9 Ibid.

10 Jerome Moross, interview by Paul Snook for WRVR Radio, 1970.

11 Moross quoted in Albert Goldberg, “The Sounding Board: Ballet Ballads,” Los Angeles Times, October 1, 1950, E7.

12 Latouche, “Items Called Ballet Ballads,” op. cit.

13 Letter from Jerome Moross to John Latouche, August 10, 1944. Jerome Moross Papers, Columbia University.

14 Cite Moross’s Modern Music article. “Hollywood Without the Movies.”

A Final Note

The publication of the complete Ballet Ballads score marks the 70th anniversary of its premiere. What is the potential for the revival, seven decades later? The musical is extremely complex, offering four separate stories with lessons on American values that can be viewed as valid today as they were in postWorld War II United States. Moross voiced the idea that colleges, universities and community performing arts companies would find Ballet Ballads an attractive and viable vehicle for inter-arts collaboration because of the equal importance and place of dance, music, and theater to the production.

This newly published score of all four acts of Ballet Ballads brings this significant American work out of the vault and into the daylight to be rediscovered and revived for new generations.

About the Author

Mariana Whitmer is Executive Director of the Society for American Music and teaches musicology part-time at West Virginia University. Among other publications, Dr. Whitmer has completed a Film Score Guide on Jerome Moross’s The Big Country (Scarecrow Press, 2012) and contributed a chapter on Moross for Double Lives: Film Composers in the Concert Hall (ed. James Wierzbicki, Ashgate Publishing, 2018). A comprehensive biography on Jerome Moross is underway.

BALLET BALLADS

A MUSICAL IN 4 ACTS

THE COMPLETE VOCAL SCORE

Ballet Ballads: The Complete Vocal Score is published in commemoration of the 70th Anniversary of its world premiere and is a true collector’s item for lovers of the American musical art form.